|

Ivory and wooden labels are

one of the most important items found in 1st dynasty royal and private

tombs.

They were attached to vessels containing various kinds of commodities

(especially oil and fat) by means of a lace passing in a circular hole

generally carved in the upper right corner (of the label's recto).

The hieroglyphic signs onto them were engraved (less frequently painted in black

and red ink) and often filled with coloured paste.

The label size ranges from about 1 to 9 cm in breadth and 1,5 - 3 mm

in thickness.

The

earliest dynastic specimen are those found in the Naqada tomb

of Neithhotep and in the Abydos tomb of Narmer; The

earliest dynastic specimen are those found in the Naqada tomb

of Neithhotep and in the Abydos tomb of Narmer;  the

Naqada tomb objects are little squares of c. 1-2 cm with numerals on

one side and the queen's name on the other one; they are directly relatable

to the pieces found by Amelineau and Petrie in the cemeteries B and U at

Abydos (Narmer tomb and 'Dynasty 0' burials) and the earliest absolute

evidence consists in the 160 + tags found by the German DAIK archaeologists

under the direction of Gunter Dreyer in the tomb U-j (Naqada IIIa2,

3150 B.C.; for these latter see G. Dreyer 'Umm el-Qaab I. Das Pradynastische

grab U-j...' 1998, p. 113-145; J. Kahl, in: Archéo-Nil 11, 2001, 102-134; id., in: CdE 78, 2003, 112-135)

. the

Naqada tomb objects are little squares of c. 1-2 cm with numerals on

one side and the queen's name on the other one; they are directly relatable

to the pieces found by Amelineau and Petrie in the cemeteries B and U at

Abydos (Narmer tomb and 'Dynasty 0' burials) and the earliest absolute

evidence consists in the 160 + tags found by the German DAIK archaeologists

under the direction of Gunter Dreyer in the tomb U-j (Naqada IIIa2,

3150 B.C.; for these latter see G. Dreyer 'Umm el-Qaab I. Das Pradynastische

grab U-j...' 1998, p. 113-145; J. Kahl, in: Archéo-Nil 11, 2001, 102-134; id., in: CdE 78, 2003, 112-135)

.

The simple little tags containing only a king's, queen's or high official's

name and the number or provenance of the goods, were used throughout

the whole dynasty (see the ink examples from Saqqara tombs i.e.Qaa11);

but already since the reign of Narmer, labels have been found to contain

what could be interpreted, yet with some caution, allusions to historical events (as battle victories, important

ceremonies, construction of buildings, payment of tributes, processions

to different shrines and other happenings).

We can divide the bone, ivory and wooden tags into year labels

(on which a royal name is incised, along with the relevant ceremonies and

other events of a single year and the indication of the product, its provenance,

quality, and name and titles of the official who stored it; these are

found only in royal or high élite tombs), celebrative labels

(which often have the royal name inscribed and were probably produced in view of important celebrations -especially feasts and construction

of buildings- but were not necessarily related to a commodity/storage) and private

labels (which were attached to middle or lower class officials'

gravegoods containers and reported the name of a product, eventually its

quantity, and the name of the functionary responsible for producing/storaging -generally the tomb owner himself-).

A broad classification of the labels in 4 groups has been deviced by

P. Kaplony (IAF I, 284ff).

The same author also divided First Dynasty labels into three main chronological

groups (old, middle, late).

The

early First Dynasty arrangement of labels in 2, 3 or 4 horizontal

registers leaves place, by the reign of Djet, to the division in two

broad vertical sectors, the right hand one containing the 'events', and

the left one containing royal name, official's name and titles

and finally the type, quality and amount of the stored commodity. The

early First Dynasty arrangement of labels in 2, 3 or 4 horizontal

registers leaves place, by the reign of Djet, to the division in two

broad vertical sectors, the right hand one containing the 'events', and

the left one containing royal name, official's name and titles

and finally the type, quality and amount of the stored commodity.

By the reign of Djet the year hieroglyph (rnpt) appears on the right

of the label, often starting from nearby the hole on the upper right

corner and ending in the middle or in the lower right corner of the

label, obviously in order to indicate that the events on its left all

happened in the same regnal year. This device is the same found on

Royal Annals (Palermo/ Cairo stone and related fragments).

The introduction of the 'time parameter' tells us that, apart from the

goods genere and the persons (king, queen, officials) and institutions

(per nswt, domains, oil presses) controlling that goods, it was also

important when these goods were confected, and this was achieved

by quoting eponymous events (i.e. the indication of a king's regnal year

by means of the mention of the main events happened during it).

The pieces considered in this corpus are those of 1st dynasty only,

thus those from Abydos cemeteries U and B remain excluded (except Narmer's

and Aha's ones); furthermore no year-label has ever been ever found dating

after the reign of Qa'a [The mention by Dreyer (in: EA 3, 1993, 11; cf. Piquette, 2004, 924) of labels from the reign of Hotepsekhemwy must be a mistake for 'seal impressions'].

A later

example is the IIIrd Dynasty Sekhemkhet's (Djoserty Ankh) linen-list

ivory label. More are known for wine and oils in later periods.

For deeper analysis of the single labels and their grouping

cf. the work of P. Kaplony (IAF I, 1963, 284ff.).

The reign of Den

is the one for which most labels are known; on the contrary, to his follower, Adjib, only one fragment can be attributed (yet there

are some feast-notices engraved on stone vessels

during this reign).

During the Second Dynasty and in following periods, some of

the informations once incised on labels began to be

engraved or painted on stone vessels (cfr. examples in P. Lacau - J.P.

Lauer 'La Pyramide a Degrée' vol. V, 1965, 88-90; also G. Dreyer,

Drei Archaisch-Hieratische Gefassaufschriften mit jahresnamen aus Elephantine,

in: FS Fecht 1987, 98-109 with no royal name).

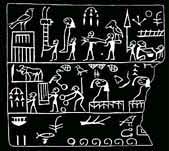

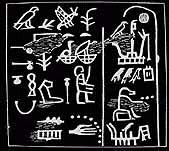

On

the Annals and on a few stone vessels inscriptions

of Khasekhemwy (fig. on the left) there is also a kind of inscriptional evidence which

is very reminiscent of the 1st dynasty labels texts (P.

Kaplony, LexAeg III, 237-8; id., IAF II, n. 1562). On

the Annals and on a few stone vessels inscriptions

of Khasekhemwy (fig. on the left) there is also a kind of inscriptional evidence which

is very reminiscent of the 1st dynasty labels texts (P.

Kaplony, LexAeg III, 237-8; id., IAF II, n. 1562).

Indeed, as noted by M. Baud (Menes, la memoire historique...,

Archéo-Nil 9, 1999, 109-147), the very method of time count

(at least that with annalistic/economic scopes) did change during the

Second Dynasty, with the adoption of biennial cattle counts (Tjenwt);

the 1st dynasty method returned in use during the Third Dynasty, as evenemential

years preserved on the cited ink inscriptions from Elephantine

(G. Dreyer, loc. cit.) do attest. Finally (from Snofrw onwards) the system was definitively re-adjusted onto the reckoning/enumeration of (usually biennial) cattle-counts.

The development of the tags before Dynasty 0 is more uncertain, and

we can be sure that they already existed from before the time of tomb

U-j: this is very important for the study of the origin of writing in

Egypt (factors which caused the emergence of writing; age of invention of this system).

Labels preserved only a 'short-hand' notation of the Egyptian language (no particles as prepositions, adverbs, pronuns), nonetheless they remain of great interest for the lexical studies (cf. J. Kahl, Frühägyptisches Wörterbuch, 2000-2004; id., Das System..., 1994; id., in: Archeo-Nil 11, 2001, 102-134).

They have a huge value in complementing seal impressions and other contemporary sources for the study of Early Dynastic religion, administration, economy and geography (place names). A recent study by K. Piquette has concentrated on the representation of human body (and parts thereof) as portrayed on these small manufacts. The last aspect which I want to analyze is the relevancy of year-labels as historical sources.

I have anticipated (cf. supra) that "events" were briefly mentioned on some portions of the etichettes, comprised within the lateral year-sign in the same way as annalistic notations on Palermo Stone and Cairo fragments appeared.

A parallel between occurrances of festivities, gods names, rituals, institutions and other features found inscribed on both year labels and late Old Kingdom annals was drawn (by Sethe, Newberry, Weill and others) as early as Annals fragments (Scäfer 1902, Gauthier 1913, Petrie 1916) and Abydos royal tombs labels (Petrie 1901, 1902) were published.

At that time there were few prejudices about the interpretation of similar documents as sheer chronicles of past historical events.

This can also be comprehended studying the first discussions of Narmer palette and related artifacts ("Monuments of the Unification").

On the other hand, the early archaeologists' eagerness for historical data, has presently been replaced with more cautious approaches which are influenced by functional, cognitive, post-processual anthropological and archaeological middle range theories.

These perspectives prompt an analysis of the context in which such documents were manufactured and which they were ultimately destined to, as well as their purposes. Representations are consequently mostly treated as elements of symbolic/ ritual/ magic

value, of propaganda of royal ideology. With few exceptions, the historical

truth possibly embedded in the inscriptions is neglected, dealt with skepticism or absolutely rejected (cf. L. Morenz, Bild-Buchstaben..., 2004, 184; C. Köhler, History or Ideology? New Relations on the Narmer Palette and the Nature of Foreign Relations...., in: E. van den Brink, T. Levy, eds., Egypt And the Levant. Interrelations ..., 2002, 499-513; T. Wilkinson, Reality versus Ideology: The Evidence for 'Asiatics' in..., ibid., 2002, 514-520; contra G. Dreyer, Egypt's earliest historical event, in: EA 16, 2000, 6-7).

There are correspondences both between the contents of inscriptions on labels and on other contemporary sources (cf. Narmer Abydos year-label, Narmer palette and Hierakonpolis ivory cylinder; gods, ceremonies and buildings mentioned on labels also appear on stone vessels inscriptions). "Historical" data provided by labels inscriptions also have interesting parallels, both in contents and in lay-out, with annalistic inscriptions of Palermo Stone and Cairo fragments (for the latter case a study has been devoted to the topic by G. Godron, in a chapter of his book "Etudes sur l'Horus Den..." (1990), p. 105-147.

Also see A. Jimenez-Serrano, La Piedra de Palermo: Tradfuccion y

Contextualizacion Historica, 2004; D. Redford, Pharaonic King-lists, Annals and Day-books, 1986).

Common events are hippopotamus hunt (on Den's labels a savage bull hunt; but hippopotamus hunt is mentioned on a seal impression of the same king and possibly on a label, Den 36), the opening of a lake at Swt-NTjerw by Horus Den (Den 56), a royal visit to the temple of Herakleopolis (Den 45), the Sed fest (Den 1, 5, 32) and

Hedj-Wrw (London fragm. - Den 25?) and more.

Mac Gregor's label (Den 31, first victory over the Eastern Desert

dwellers/"Troglodytes") was connected in the past to the victory over the Jwntyw recorded on Palermo Stone rc. line III, case 2.

Annals' year cases are indeed an abbreviated version of labels (event portions).

It has been said about the formers' possible religious/magic value, aside the more practical one: it must be equally remarked that also labels might have been considered by ancient Egyptianto to retain something more than a mere administrative utility (that of controllers

of the commodities stored in the containers which they were attached to).

We know that writing in Egypt could be magically endowed of the same properties that real objects and reality itself had. At least as early as the 1st Dyn. the hierogliphic signs could be object of "mutilations" (seal impr. from the Naqada mastaba, Kahl, SÄK 2000)

in order to control their magical, potentially harmful, power.

Labels were, in my opinion, already conceived with the same properties that the later texts and depictions in the tombs would have: the "events" inscribed (always positive facts, with only a few possible exceptions -of doubtful reading)

would magically prompt the Maat's will, thus reinforcing and eternally reproposing victories over the enemy and evil (apotropaia), fests, rituals and other "events".

Additionally, inscriptions listing the commodity type and quantity did not only serve as a means of control of containers before these ended up in the tomb: they also acted as the lists of offerings found on tomb stelae (since late 1st Dyn.,

Helwan slab stelae) and then in Old Kingdom tombs niche-panels and wall paintings did.

A magical substitute of material offerings for the afterlife of the deceased. If it wasn't so, then why would the labels be left attached to the vases or gathered in boxes after the containers had been placed into the tomb?

My main interest is in the historical events, officials' titles and

names of establishments and buildings depicted on the labels, as well

as possible comparisons of these with the ones in the Annals.

Furthermore the detailed analysis that I aim to complete should also

clarify the relative chronology of the labels for each reign.

I have tried to include in the corpus only labels (either Kaplony's

'jahrestafelchen' or 'festtafelchen'), excluding similar pieces as ivory

or wooden parts of boxes, combs, gaming pieces or the like; when the

object is not a label I do remark it.

The comprehension of the archaic writing is still very hard, but great

progresses have been made in the last decades by the efforts

of various egyptologists, particularly Peter Kaplony, Wolfgang Helck

and, more recently, Jochem Kahl (1994, 2003-on).

It's impossible not to mention again the German excavations at Abydos

which have yielded invaluable amount of new data from cemetery U, B

and Umm el Qaab 1st-2nd dynasty royal tombs; some of the labels here

listed have been recently found during these works of the German

teams directed by Gunter Dreyer and readily published in the annual review

of the Deutsche Archaeologische Institut of Cairo (1982- to present):

Dreyer et al. in MDAIK n. 38 (1982), 46(1990), 49(1993), 52(1996), 54(1998),

56(2000); 59(2003); Dreyer 'Umm el Qaab I'(1998); many more labels have been found,

especially in the tomb of Qa'a, (E.-M. Engel PhD thesis) but they are yet unpublished.

Therefore the bases of this corpus remain the publications of the excavations

at Abydos by W.F. Petrie (Royal Tombs I, II, Abydos I) and those at

Saqqara by W.B. Emery (Hor Aha, Hemaka, Great Tombs I, II, III). |

The

earliest dynastic specimen are those found in the Naqada tomb

of Neithhotep and in the Abydos tomb of Narmer;

The

earliest dynastic specimen are those found in the Naqada tomb

of Neithhotep and in the Abydos tomb of Narmer;