SAQQARA

Early Dynastic monuments (Dynasties 1-3)

PART I: GENERAL INTRODUCTION ON SAQQARA AND MEMPHIS

The site of Saqqara is the central portion of the Memphite necropolis

which stretches from the northernmost sites of Abu Rawash, Giza to

Zawiyet el Aryan, Abusir, Saqqara, South Saqqara and finally Dahshur

and Mazghuna in the south, for more than 30 kilometers.

Memphis was founded at the end of "Dynasty 0" or beginning

of the First Dynasty and was the capital of Egypt at least since the

early Second Dynasty to the Eighth Dynasty (with the exception of

some reigns, particularly in the IVth Dynasty) and again it became

a major center in the XIIth Dynasty; after the second Theban reconquest,

its importance began to increase once again with Ahmose and still

more from the reign of Thutmosis III to Akhenaton; Thutmosis III resided

in Memphis for the most of his reign, especially in the period of

the Asiatic campaigns; in this period the riverine harbour Prw-Nfr

and the garrison Pa Khepesh were particularly active; most

of the early 18th Dynasty ereditary princes resided in the city during

their youth, this fact certainly depending on the presence of very

important structures of instruction like the House of Life, the temples

and the garrison.

After the short-lived Akhetaton (Amarna), Memphis returned to be officially

the capital of Egypt in the reign of Horemheb until the construction

of Piramesse. Under the great Ramses II, despite the new-born capital

in the Delta, Memphis knew another period of splendour for commercial

and political reasons; Ramses II lived here before Piramesse was completed;

his son (High Priest of Ptah) Khaemwaset restored many monuments of

the necropolis, as attested by the inscriptions he left on some pyramids

at Abusir and Saqqara (cf. the fragmentary one up on the south side

of the Unas pyramid); he was buried in the Serapeum in the 55th year

of his father's reign.

In the late period the city passed through alternating phases as the

new building projects of the Tanite and Saite pharaohs and the strangers'

dominations of Ethiopics, Assirians and Persians.

Known as 'Balance of the Two Lands' (Mekhat Tawy)

and 'White Wall' (Inbw Hedj), it received only in the Middle

Kingdom the denomination of Men-Nefer, after the name of the

Pyramid and funerary complex of Meryra Pepi (I) of the VIth Dynasty;

and from 'Men-nefer' the present Graecized name 'Memphis' originated

(indeed Mennefer became largely used only since the 18th dynasty,

because in the Middle Kingdom the name of the Teti pyramid Djed-Iswt,

was preferentially adopted to designate the urban center). For further

names of the city as 'Ankh Tawy', 'Njwt Heh' and others cf.

Zivie, in: LA III, 24-26.

The site of Memphis was identified in late 1500 by the traveller Francois

de Pavie and, few later, by Jean de Thévenot (Zivie, op. cit.,

33, n. 219); since the first half of the '700, R. Pococke, who visited

Egypt in 1737, basing on the classic writers Strabo and Plinius, correctly

assumed that the site of the ancient capital had to be located around

the modern village of Mit Rahina. This is situated circa 2,5 km east

south-east of the Pyramid of Djoser, and 2 km east of that of Pepi

I; (the ancient site was obviously much wider than the actual ruins

field at Mit Rahinah - Bedrashiya).

The earliest site of Memphis (Dyn. 1-3) laid instead just at the feet

of the North Saqqara archaic necropolis plateau, below the 1st Dynasty

mastabas, therefore under the south-west part of the modern village

of Abusir.

Also the necropolis of Middle Saqqara (the area extending around the

two Step Pyramid complexes) is actually nearer to the village of Abusir

than to the modern hamlet of Sakkara (which is in front of the site

of South Saqqara).

The increasing height of the Nile flood and the eastward shift of

the Nile-bed, alongside other factors, resulted in the abandonment

of the site of the early capital located under Abusir in favour of

the new and more eastern settlement located near Mit Rahina, which

seems to have occurred sometime in the late Third Dynasty.

For various reasons (first of all constructional overcrowding,

long lasting reuse of building materials, the massive accumulation

of Nile deposits and modern frequentation and exploitation), the field

of ruins in the site of the ancient capital has revealed to be rather

poor of archaeological remains, especially of Old Kingdom age buildings

(but a good number of Old Kingdom pots has been found). However the

necropolis of Helwan and Saqqara,

east and west of the city, were undoubtly founded in the Dynasty 0

and in the early First Dynasty respectively.

Herodotus (II,99) attributed to the legendary Menes the foundation

of this new Capital which substituted the Upper Egyptian center of

Thinis. Manetho labelled as 'Thinite' the first two dynasties, but

there would be much to speculate on this problem. The southern Thinis

and its necropolis, Abydos, surely retained their importance for the

whole age of the so called 'Thinite kings', but it can be assumed

that Memphis started to be de facto the main center of the

administration of the country at least with Hotepsekhemwy, but very

probably (and to a high level) already at the beginning of the First

Dynasty; there is no evidence of a royal tomb in Abydos for any ruler

of the first half of the Second Dynasty; on the other hand, the substructures

of the tombs of kings Hotepsekhemwy (A)

and Ninetjer (B) (1st and 3rd rulers of

the 2nd Dynasty respectively) were discovered south of the Step Pyramid

complex (cfr. below) and now, probably a third

gallery complex (C) has been found few to the south, in the eastern

New Kingdom tombs-field delimitated by the complex of Sekhemkhet and

the remains of the monastery of Apa Jeremias (this new found tomb

could hardly be a private one; the early 2002 dutch excavations seem

to have clarified its features and its royal character).

A royal cult estabilishment (of Den's reign) possibly consisting of

a (perishable material ?) enclosure surrounded by middle class officials'

tombs (as n. 59 of Ipka), was

reconstructed by Kaiser (M.D.A.I.K. 41, 1985 p. 47-60) on the basis

of excavations and plan of R. Macramallah (1940); the rows

of tombs are N and NW of the Serapeum.

Whether Kaiser's hypothesis of a rude Talbezirk was valid, this would

show that the royal authority, activities and presence in Saqqara,

and thus in Memphis, were already concentrated there at least since

the middle First Dynasty.

The imposing size of the First Dynasty mastabas built on the eastern

edge of the desert escarpment overlooking the capital, is a clear

sign of the importance of this urban center which was much more in

the core of the commercial circuit of interchange with the Near Eastern

peoples than the remote Thinis could ever be; this soon began to lose

its political importance and only maintained a religious and cultual

authority as the center of the archaic sovereigns' burials and, since

the late Old Kingdom, as the site of the tomb of the god Osiris (identified

in the Umm el Qa'ab tomb O, of Horus Djer; Dodson,

KMT 8:4 37-47), and consequently a frequented destination of

piligrimage until the dawn of the modern age.

The importance of the Memphite location resided in the easy control

of the riverine and desert trade; indeed this had already been a major

factor for the rise of the predynastic center of Maadi, just near

to the Wadi Hof and Wadi Digla, which open towards the Delta and Near

Eastern routes.

On the other hand the early cemetery of North Saqqara must have been

regarded as a holy place during all the Dynastic period, because as

Emery wrote in 1958 "... it is a curious fact that the archaic

necropolis is the only part of Sakkara which has not been re-used

as a burial ground for later periods" (Emery, GT III, 1958,

2); there are indeed some exceptions in the central area cleared by

Quibell in 1912-14 and near S3507 (see below).

The necropolis of Helwan,

although with less impressive tombs (private burials of middle-high/

middle-low classes) than at Saqqara, was founded some generations

earlier, as attested by certain Dynasty 0

royal names on jars (Nj-Neith, Ka, Narmer); the officials buried here

witness their kings' evident interest in controlling the trade of

various commodities to-fro the Southern Palestine and beyond.

The effect of the rise of Memphis must have been an outstanding one

when we look at the impact it had on the sites of the region: most

of them declined at the beginning, during or at the end of the First

Dynasty as the Dynasty 0-1 cemeteries from Tarkhan to Tura, Zawiyet

el Aryan and Abu Rawash demonstrate (but in the latter site to a very

slight degree, if not at all, as the 1st/2nd and 4th/5th Dyn. Tombs

Klasens excavated and the Lepsius I Mudbrick

Pyramid, Ed-Deir and Djedefra's

pyramid complex do attest).

Saqqara owes its name to the necropolis' archaic falcon-god

Sokar (not to the medieval tribe of the Beni Sokar).

Despite the name of the necropolis, the modern village of Sakkara

is situated in the shadow of the palms in front of the archaeological

site known as South Saqqara, where Shepseskaf and then Djedkara Isesi

first built their tombs.

The sole Archaic Cemetery of the élite at North Saqqara covers

an area of more than 350.000 m².

The earliest known mastaba is situated in the North Saqqara plateau

and dates to the reign of Horus Aha (S3357); more mastabas were built

north and south of it in the following reigns of the First Dynasty,

exhausting, by the reign of Qa'a, all the available space on the eastern

edge of the escarpment.

Already since Horus Djer more than one huge mastaba was built in a

single reign (S2185, S3471); the apex was during the reign of Den,

in the middle of the First Dynasty, and under Qa'a, at the end of

the same dynasty.

S3507 and S3503 respectively produced prevailing inscriptional evidence

with the names of Queen Herneith and Merneith, while no tomb has yet

been found of any individual relatable to the reign of Horus Semerkhet

(who is instead attested at Helwan).

The southernmost tombs of this kind were built in the area east of

the pyramid of Teti (one was found just beneath the house of the Office

of the Antiquities) and Lepsius XXIX (Merikara ?), while the northernmost

ones (S3041, 3043, 3038, S3111) are just at the northern end of the

North Saqqara ridge (for all the mastabas see below).

After the huge mastabas of the reign of Den (3035, 3036) the size

and wealth of the tombs began to decrease; but one of the tombs dated

to Adjib, S3038, though of medium size, reserved an unexpected surprise

to the excavator W.B. Emery: it revealed three constructional phases,

the first one of which consisting of a 8 steps brick-structure (less

than 3m high) which was considered the conceptual forerunner of the

Step Pyramid (sand mounds are known to have been included in the inner

parts of other tombs as S 3471, S3507, Bet Khallaf K1, Abydos Umm

el Qaab Z, just above the burial chamber; these mounds are thought

to be related to the mythical primeval hill of creation, thus being

religious symbols of post-mortem rebirth).

There is no doubt, after almost 70 years of debates,

that the mastabas in object belonged to the highest officials of the

'Thinite' state administration. A thorough analysis of the debate

about the site of the royal tombs and of the so called 'cenotaphs'

(Saqqara vs Abydos) is out of the aims of the present article (but

cfr. the brief summary below).

It has been synthesized and discussed several times (cfr. bibliography;

A. Tavares in K. Bard ed. 1999, 700-704; Emery, Hor Aha, 1939, 1-7;

id., GT II, 1954, 1-4; id., GT III, 1-4; Lauer, Hist. Monum., 1962,

passim); until the IV-Vth Dynasty the royal tomb remained neatly separated

from the private ones; at Saqqara only with the reign of Unas the

king's complex began to be surrounded by private tombs (but in this

we are not considering the so called tombs of the retainers around

the Abydos royal tombs and enclosures).

However the recent excavations by K. Mysliwiec west of Djoser's

complex (reports in PAM 8-13, 1997-2002) seem to point out that early

Third Dynasty tombs were already built there before the Step Pyramid

Complex underwent its latest constructional phases; if confirmed,

this would mean that it was already with Netjerykhet/ Djoser that

the trend of private cemeteries bordering the royal funerary complex

was first introduced (J. van Wetering, n.p.; id. 2002).

It is pure speculation to advance that the tradition might have begun

in honor of a worthy personage like Imhotep, like Lauer would also

think; Emery thought instead that Imhotep's burial was to be searched

for in the western part of the North Saqqara élite cemetery

(around S3518) where he found the late period animals catacombs and

many attestations of worship of the deified Imhotep (bronze statuettes)

in the second part of the 1960s (see below).

In the Second and Third Dynasty, the officials were

forced to move their site of burial westwards, in a recessed position

from the 1st Dynasty tombs line. There was no more space left on the

'panoramic' eastern border which had been completely filled up with

earlier tombs; therefore the adiacent central area of the North Saqqara

plateau was chosen for the mastabas of the Second and Third Dynasty

élite members.

Few eastern archaic tombs were reused and rebuilt in the IInd and

IIIrd Dynasty (as S2171, 1st/2nd dyn).

The new Second Dynasty tomb (C),

probably a royal one (Sened? see also below),

found east of Horemheb's sepulchre in the NK necropolis, must demonstrate

that, contrarily to the Ist-IInd dynasty outcrop of the Archaic necropolis

known down towards the Abusir lake (cf. JEA 79, 1993, 25), there was

no continuation of the Early Dynastic tombs line towards Middle Saqqara;

the southern part of the cemetery was destined (since the Second Dynasty)

to the royal tombs only, and the contemporary private burials

could not have been built in this area (not before the Third Dynasty,

cf. below).

PART II: FIRST DYNASTY MONUMENTS

The general development of the private tombs architecture in the Early

Dynastic period follows that of the royal Upper Egyptian monuments;

indeed it has been repeatedly remarked that the constructional techniques

of the Memphite tombs of the elite appeared to be more evolute than

those applied at Umm el Qa'ab, Abydos; J.P. Lauer and W.B. Emery compared

the sheer size of the mastabas of Saqqara with those of Abydos, showing

that these latter, evidently smaller and less complex in architectural

design, had to be nothing more than cenotaphs, the true burials being

those at North Saqqara.

But since 1966 Barry J. Kemp (and few later W. Kaiser) pointed out

that the Abydos tombs could not be directly compared in size and monumental

aspect with the Saqqara mastabas: in fact almost all the Umm el Qa'ab

burials were only a part of the royal funerary complex also consisting

of the associated "forts", large mudbrick enclosures (open

courts) of possible funerary function built less than a couple of

miles to the north and surrounded, like the tombs, by the small "tombs

of the courtiers" (small rectangular tombs sometimes provided

with a raw stela).

The number of sacrificed retainers buried around the Abydene tombs

always surpasses (even without considering those around the enclosures)

those around the Saqqara mastabas. And at Abydos the custom lasted

for more reigns than at Saqqara, where it already declined in the

middle of the (Ist) Dynasty.

Finally the stelae with Horus names of 1st Dynasty kings were only

found at Abydos.

Today a good push towards the final, almost unanimously accepted conclusion

that the Abydos tombs are those of the kings (while the ones at Saqqara

belonged to their highest functionaries and eventually relatives),

has arrived after the reprise of the excavations at Abydos by the

German archaeologists directed by Kaiser and Dreyer (late '70s on);

the general opinion has returned to embrace the idea which had emerged

after the campaigns of Petrie, a century ago: the Ist Dynasty kings

(alike some of Dynasty 0 and perhaps two of late IInd Dynasty)

were buried at Abydos. Here the funerary

enclosures in the North, at Deir Sitt Damiana and Kom es Sultan,

served to the cultual and monumental aspect, while the Umm el Qaab

tombs were the place in which the kings were buried; Petrie's escavation

of tomb Z (Djet), the one where the less elusive traces of the possible

tomb-superstructure remained, suggested that a low and almost flat

mound did emerge at the surface level, supported by the wooden roof

of the central burial chamber; around and above this tumulus there

was the sand and rubble which formed the filling of the true superstructure

of the tomb; this consisted in a slightly inclined perimetral mudbrick

wall of modest height which contained the loose filling with a probable

round-topped aspect (as in some subsidiary burials which have fully

preserved their superstructure like those around the Abydos 'forts',

or around the largest mastabas at Saqqara and Tarkhan); therefore

the above-ground visible part of the tomb was nothing like the massive

and impressive building Reisner had hypothesized; the German re-excavations

have confirmed and refined this theory, finding comparable hidden

tumuli also in Qa'a's (Q) and Den's (T) tombs (Dreyer, in: MDAIK 47,

1991, 93-104; id., in: MDAIK 49, 1993, 57; Kaiser, Zu Entwicklung

und Vorformen der Fruhzeitlichen Graber..., in: BdE 97/2 =Mel. G.

E. Mokhtar, 1985, 25-38; Petrie, Royal Tombs I, 1900, 9; also see

Badawy, in: JNES 15, 1956, 180-3; also cf. above for the sand mounds

found within Saqqara S3471, S3507, Bet Khallaf K1).

The private tombs of North Saqqara underwent some structural

development which, as I ve anticipated, followed the similar transformations

in the Royal tombs. But the palace façade outer wall, the inner

tumulus and the eventual cult chapel or true temple were all incorporated

in one complex, always surrounded by a plain enclosure wall.

Contrarily to the archaeological evidence from Tarkhan and Helwan,

which has provided us with inscribed material dated to Dynasty

0 rulers and Narmer, at Saqqara only one stone vessel with Narmer's

serekh has been found (cf. PD IV.1, pl. 1.1; PD IV.2, 1-2).

S3357 is the earliest (known) mastaba of the necropolis,

the only one dated to Hor Aha: this demonstrates

that the administrative apparatus dislocated in the newly founded

city (already the capital ?) was rapidly increasing in size and complexity

during the subsequent reigns. The monumental aspect of this tomb,

despite its private ownership, indirectly emphasized the king's power.

The structure of the tomb resembles the roughly contemporary giant

mastaba at Naqada,

also dated to Aha (but surely earlier in his reign) and entirely built

on the ground level (whereas S3357 already had the burial chamber

dug in a central pit). S3357 (c. 41,5x15,5m) was discovered in 1936

and published in 1939, when more tombs had already been brought to

light (but the war delayed their publication of 10 years); it was

nearly soon understood its early date (to the reign of Aha who was

"Menes" in Emery's opinion). The mastaba was surrounded

by two plain enclosure walls (thickness: 0,75m the outer and 0,55m

the inner one, 1,2m distant from eachother); no subsidiary burial

was found around it (but scattered bones from the subterranean rooms

suggested to Emery that some (slain?) retainers must have been buried

in rooms 1,2, and 4,5 to the S and N of the burial chamber).

The enclosure walls, preserved to a height of few more than half a

meter, were both covered with mud plaster and faced with lime wash;

the niched façade was c. 2,5m thick, preserved at a maximum

height of 1,75m, coated with mud plaster and white lime stuccoed.

The superstructure consisted of a niched mastaba with 27 magazines,

the central five built above the 5 underground chambers (19m from

N to S), the central one of which, at 1,35m below the ground level,

was the burial chamber.

The roofing of the substructure was formed by long poles running E-W

under the floor of the central magazines of the mastaba; these beams

(10cm in diameter, spaced at 15cm from eachother) supported the planks

(25cm wide for 12cm thick) set perpendicularly to them.

Among the finds of the tomb there were hundreds of cylinder pottery

jars with ink inscriptions reporting the king's serekh, the contents

and its provenance (taxation sketches, 70-74, pl. 16: 460 groups of

which 208 in pl. 20-24); on the remaining pottery, mostly in fragments

for the collapse of the roof, only 6 (incised) potmarks were reported;

interesting are the cylinder seal impressions (Hor Aha, 1939, 19-33),

some of which already in use at the time of the burial of Neithhotep

at Naqada, many other ones of a new type; their variety was also greater

than that of the types recorded by Petrie at Abydos B19-10-15 and

nearby burials; n. 19 (ibid., 31, fig. 31) possibly named Djer, while

many others introduced the motif of the crouching lioness before the

UE shrine; others had only two rows with Aha's Horus name or with

this latter accompained by the private names (?) Ht and Sa-St;

the sealing n. 32-34 were perhaps older (Dynasty

0 = Naqada IIIB or even earlier) being

similar to those found in 1990s by G. Dreyer in Abydos Cemetery U

(Hartung, MDAIK 54, 1998, 187-217; id., SAK 26, 1998, 35-50; Kaiser,

MDAIK 46, 1990, 287-299, fig.2) and to that from Abusir el Meleq t.

1035 (Kaplony, IAF III, 71) dated to Naqada IIIA1-2.

Four pottery rhino horns were found in magazines X, U, V, F (ibid.,

71ff., pl. 17); furthermore also pieces of furniture, flint tools,

palettes, stone vessels (ibid., 34ff., pl. 12-15A) and, in the undergreound

chambers, human remains from different individuals' skeletons were

discovered.

Contrarily to the Naqada Mastaba and to Abydos B19/16 complex, no

inscribed label was found in S3357.

Few years later, the removal of a Third Dynasty superstructure north

of the tomb led Emery to discover what he called a "Model

Estate" in three parallel alleys: at the northern end of

the outer ones there were two model granary buildings; to the north,

it had been already discovered in 1937 a funerary boat (Hor Aha, 18,

pl. 3, 8) which was 35m north of the tomb (under the south part of

the 2nd Dynasty Mastaba S3025) encased in mudbrick like those found

at Abu Rawash, Abydos and Helwan.

In the next reigns (Djer, Djet, Merneith) the chamber is dug deeper

in the gravel (as at Abydos) and the magazines number increases (QS

2185, S 3471, S 3504, S 3503), while in the reign of Den, after the

S3507 (Queen Herneith ?), there is the introduction of the stairway

as in S 3035 belonging to the chancellor Hemaka (which is paralleled

by the roughly contemporary equal innovation in the Umm el Qaab tomb

T of Abydos).

S2185 was cleared (in 1912-14) and published by Quibell

(Archaic Mastabas, 1923, 5-6, pl. 5-10; size m x ).

Its superstructure was badly destroyed and the underground chambers

contained stone vessels, copper and flint tools and clay seal impressions

with serekhs of Horus Djer.

The small pit S2171H was dated to the same reign and

found by Quibell (op. cit., 6-7, pl. 11-13) underneath the Second

Dynasty tomb S2171. It contained many stone vessels, some furniture

fragments, flint, beads, and two labels inscribed with the name of

Djer: an ivory one incised and a

wooden one painted.

S3471 (m 41,25x15,10) was found by Emery in far a worse

state of preservation than S3357; the 29 magazines of its superstructure

only contained scattered and fragmentary stone/pottery vessels, while

the substructure had been burnt (in the excavator's opinion the fire

had occurred not much later than the First Dynasty and was probably

set by the same plunderers aiming to hide their deed).

The floor of the burial chamber (O, m6,3 x 4,0) was at a lower dept

(3,5m from the ground surface) than those of the six rooms N and S

of it. These latter had been dug separately and no passage between

them existed other than that practiced by the ancient plunderers.

The fire spared only few objects of deteriorable material as mud-seal

impressions (wherein Emery read Djer's serekh) and furniture, whereas

no inscribed label was found.

Anyway one of the seven subterranean chambers (S, just south of the

burial chamber, O) contained an impressive amount of copper in form

of more than 70 vessels (beaten copper jars, ewers, bowls and dishes

of 7 distinct types; cf. Emery, Great Tombs I, 1949, 24ff., pl. 5,

8A; for a similar treasure from the Abydos tomb of Djer cf. Serpico-White,

in A.J. Spencer, Aspects, 1996, 128-139) and hundreds of copper knives,

saws, adzes, hoes, chisels, piercers, bodkins, needles and rectangular

plates originally contained in wooden boxes (GT I, 24-57, pl. 9A,

9B, 10; Emery, ASAE 39, 1939, 427-437); there were also several fragments

of wooden furniture, roughly rectangular stone palettes, (one, ibid.,

60, had been softly incised with a figure of a standing king raising

a mace in his hand towards a Libyan (?) captive at his feet; on the

right the forepart of a lion with two hearts nearby its mouth); then

copper, leather and ivory bracelets, game pieces, some flint knives

and scrapers; finally few ivory vessels and more pottery (some with

potmarks in a larger variety than in S3357) and stone vessels.

In

the reign of Djet (to which also belonged the Nazlet Batran,

Giza Mastaba V and probably the biggest Mastabas at Tarkhan 1060,

2038, 2050) at Saqqara the large tomb S3504 (Sekhemka-Sedj)

was built (49,45x19,95m; 56,45x 25,45m incl. the enclosure).

In

the reign of Djet (to which also belonged the Nazlet Batran,

Giza Mastaba V and probably the biggest Mastabas at Tarkhan 1060,

2038, 2050) at Saqqara the large tomb S3504 (Sekhemka-Sedj)

was built (49,45x19,95m; 56,45x 25,45m incl. the enclosure).

Emery found it on Febr, 1, 1953 and the works lasted until April 5;

it was rapidly and efficaciously published in the next year (GT II,

1954, 5-127, pl. 1-37).

The superstructure contained 45 magazines; around the niched façade,

at the base of the main wall of the mastaba, it was built a low bench

surrounding the whole superstructure; on this platform were laid several

clay modelled bull's heads provided with real horns (about 300); the

façade was completely white lime washed except for the innermost

panel of the large niches which were painted in red. The wall of the

mastaba is 2,9m thick and preserved up to the heigth of 3,35m; the

large niches are 2m wide and 1,1m deep, while the small niches are

0,45 x 0,25m.

Around the mastaba runs a continuous enclosure wall (0,95m thick,

max. height 0,73m) beyond which there is a single row of 62 subsidiary

burials dug in 2 continuous trenches compartmented by mudbrick walls:

one trench runs on the western and southern sides and the other on

the northernmost three quarters of the eastern side (on the north

side there's instead another wall); each subsidiary tomb has its own

separate superstructure, a round topped, rubble filled midbrick mini-mastaba

of 1,70 x 1,45m and less than half a meter in height. The retainers

were slain at the time of the burial of the tomb's owner; they were

servants, attendants, a dwarf (subsid.

tomb 58) and some dogs.

Interestingly enough S3504 was plundered and burnt not long after

the burial period and the terminus ante quem is provided by

the certain signs of reconstruction and repairs which were accomplished

under Qa'a: the burnt burial chamber was cleared and reinforced by

a thick (1,2m) mudbrick wall which reduced its area.

The original substructure was a 22,6 x 10,2m trench, the central part

of which was dug at 3,1m below the ground level forming the burial

chamber (originally 7,1 x 5,7m); two large rooms on the N and two

on the S of the burial chamber occupied the same pit of the latter

but at more than 1m higher in level; on this same floor eight smaller

magazines on the E and eight on the W sides were separately dug.

One curious feature Emery noticed on the south wall of the burial

chamber was a recessed niche at some cm from the floor which probably

had housed a wooden panel as those of the 11 niches of Hesyra's tomb

S2405; at the foot of the wooden panel recess, an bricked offering

cache contained the skeletons of two gazelles (GT II, 11f., pl. 14).

The superstructure magazines contained a large amount of stone and

pottery vessels (for the first time with pot- marks in a noticeable

quantity and variety, ibid., fig. 100-102), many clay seal impression

of jars, flint, furniture, game pieces (marbles, a lotus-like pawn,

an ivory dice-stick), arrow heads, a gold ring, and an wooden

label (ink).

Nine more labels were found in the burial chamber (OO) and few others

in the surrounding underground rooms; also an ivory (wand?) inscribed

with Djet's serekh followed by the name of Sekhemkha-Sedj came from

OO as well as human bones of an approx. 26 y.o. adult, scattered in

the burial chamber with a vast mass of broken wood furniture, pottery

and stone vessels fragments, sandals, toilet sticks, copper tools,

leather, gold inlay and objects of unknown use (see ibid., pl. 26-35).

The inscriptional material (ibid., 102-127) thus consisted of seal

impressions; incised and painted short texts on stone vessels; ink

inscriptions (oil income) of Sekhemkasedj on pottery jars (similar

to those of Aha on S3357 cylinder vessels); important ivory and wooden

labels [ibid., fig. 105 (the oldest

known example with the rnpt-year sign on the right), 108,

109, 110-112, 113,

114, 115,

116, 117-119, 120,

121 (115-121 name the Per-Hedj treasury), 122

(rnpt-year sign on the right), 123

(this one is of Qa'a's reign), 124

(inventory of commodities for the Per-Desher ?), 125

(perhaps arranged in five columns)]. A further label of Djet and Sekhemka,

perhaps also from this tomb and similar to the one in fig. 105, was

published five years later by Vikentiev (ASAE

56, 1ff.).

The reign of Den marked an important step forward, not only

in funerary architecture development, but also in the progress of

the State and of its subsystems (administration, economy, crafts,

religion, kingship) as witnessed by the proliferation of titles of

nobles, officials and lesser aristocracy (stelae of Abydos and Abu

Rawash), the increment in the use of seals and labels,

the arts masterpieces (stone vessels fashioned

in daring shapes and materials), new attributes of the king(ship)

(the new 'Nswt-bity' royal title, canonization of king's role, attire

and attitude; cf. H. Sourouzian, in: Kunst des Alten Reich = SDAIK

28, 1995, 133-154; id., in: Grimal ed., Les Critères de datation...,

= BdE 120, 1998, 305-352).

By far most of the known First Dynasty private tombs date to Den's

reign (esp. at Saqqara and at Abu Rawash).

S3503 (42,6x16m) (GT II, 1954, 128-170; Helck, in: LÄ V, 290-1, fig. 4) Situated immediately North of S3504 and in line with the latter tomb axis, S3503 was surrounded by 20/22 subsidiary burials, the enclosure wall and, on the north side, a brickwork casing for a funerary boat was found beyond the subsidiary burials A-C, south of S3500 (it was c. 13m north of S3503, and its maximum length was 17,75m: 'unlike the boat graves of tomb 3357 and 3036 it was not sunk below ground level and the brick casing rests entirely on the surface', op. cit., 138, fig. 203).

The tomb had 9 niches (10 bastions) on the longer side and three on the short ones; some of them retained traces of painting; at the base of the niches Emery encountered post-holes, as in S3357 and S2185: these cut the pavement mud plastering (GT II, 131f., fig. 201) and Emery interpreted them as traces of the workers'/painters' supporting scaffolds.

Some boat models and other pottery broken objects were found in subs. pit F (op. cit., 147-8), while the occupant of pit T had a copper blade still at his ankle, and that of pit A kept a strange copper (surgical?) tool in a wooden box found close to his skeleton.

Most of the superstructure (21) magazines were well preserved but plundered, some were collapsed or had been set on fire (soon?) after the plundering.

The substructure pit measured 14,25 x 4,5m and was divided in 5 chambers, the central one (L) was the burial chamber (op. cit., p. 141, fig. 204): this was 4,80 x 3,50 in size and contained fragments of a wooden sarcophagus (c. 2,7 x 1,8m) on which base few small parts of human bones and gold foil remains were found scattered.

The chamber also contained remains of a funerary meal (animal bones from 6 stone bowls/jars and a pottery vessel found beside the sarcophagus), pottery vessels near the walls, traces of wooden and basketwork chests, three fragmentary wood canopy poles.

Few potmarks were found on large wine jars (fig. 223); most of the stone vessels dated to the reign of Djer, as also the seal impressions (Kaplony, IAF I, 79-80). At least 2 seal impressions were found alternating the serekh of Djer with a serekh-like device containing the name of Mer-Neith (with a topping Neith standard instead of the Horus falcon; cf. fig. 226 and pl. 55; this recalls the similar name of Neith-Hotep in the serekh); Merneith's name was also traced on two of the stone vessels forming the funerary repast in room L (cf. p. 142, fig. 205-6, with khenty).

S3507 (total size: 44,35x22,25m; only the mastaba: 37,9x15,8m)

is a pre-stairway mastaba dated to the reign of Den; perhaps

its owner was Queen Herneith, a wife of Djer died in the first

part of Den's reign (GT III, 73-97).

The tomb was found in an area where also minor 3rd Dynasty tombs had

been located; some of these had to be removed during the excavation

being built above parts of S3507. This was the last mastaba of the

1st Dynasty Emery cleared near the eastern escarpment of the cemetery

(December 31, 1955 - March 3, 1956).

The superstructure is the best preserved of all, in some points up

to c. 2,5m (F.R. photo 1; F.R.

photo 2 + plan);

it is divided into 29 magazines by crossing walls (0,65m thick). Inside

one of the magazines it was found a limestone

slab (width: 0,395m, thickness: 0,41m) which had been used to

retain the west wall of the shaft of one of the small Third Dynasty

tombs built over S3507; this slab is decorated in relief with a scene

consisting of two standing kings with long beard, red crown and Heb

Sed robe on the right and a baboon surrounded by four birds (hieroglyphs)

on the left; Emery suggested it was perhaps a trial piece and certainly

a reuse in the 3rd Dynasty tomb, dating it to the period of S3507

and however not after the end of the Second Dynasty (ibid., 78, 79,

84; cf. also A.J. Spencer, British Museum, 1980, n. 16. BM 67153);

indeed the framing band of the stela and the shape of falcon and owl

recall that of Qa-Hedjet in Louvre

(which is however far better refined and certainly somewhat later).

The tomb is surrounded by an enclosure wall which has a gateway (1,65m

wide) nearby the southern end of the east wall; 0,65m beneath this

entrance Emery excavated the tomb of a saluki dog, the guardian of

Herneith's sepulchre (ibid., pl. 91); no other subsidiary tomb was

found around the mastaba.

At the feet of the mastaba niches there is a low bench as in S3504,

which also has some clay bull's head with real horns; the corridor

(2,9m wide) between the bench and the external enclosure has a green

painted mud paving.

The substructure consists of a pit (size on ground level: 5,25x3,15m;

depth: 4,75m) with a ramp on its N side and two roofs: the first one

few cm above the ground level and the second one at 2,50m from the

bottom of the pit.

The southern part of the lower roof is occupied by two rock-cut pilasters

on which a limestone lintel had been laid; this latter is decorated

with a row of hammered out crouching lions (ibid., pl. 96; Archaic

Egypt, pl. 32); the lintel supports a stone roof covering the southern

part of the burial chamber where pottery and stone vessels were found.

In the northern part of the burial chamber there were remains of the

wooden coffin and human bones; around the sarcophagus small dishes

and food (ox bones) had been set into little brick-niches; there were

also many remains of jewelry (in faience, lapislazuli, carnelian,

gold and broken bracelets of ivory and stones) gaming pieces and flint.0.

Above the higher roof of the burial pit Emery cleared "a rectangular

tumulus of sand and rubble, cased with a single layer of bricks laid

in tile fashion" (ibid., 77, 79; size: m10,50x9,20; max height

1,10m).

Inscriptions (ibid., 93ff.): seal impressions of Den and Sekhka;

names and titles scratched on pottery (one with Her-Neith, another

with Sma Nebwy), serekhs of Den with indication of northern or southern

oil incomes (painted on jars), once again 'Sma Nbwy' incised on a

ivory cylinder vessel and 'Hwt-Mr-Khentyamentyw' on an ivory tile.

P. Kaplony (IAF I, 1963, 90-95) dated the tomb to the same period as Umm el-Qaab Y (Merneith).

S3506 (47,6x19,6m)

S3035 was discovered by Firth in 1930 (Firth, ASAE 31,

1941, 47), but it was Emery to complete its clearance.

The finds from the very large tomb of Hemaka (m57,3

x 26; cf. the size of the huge mastaba at Naqada, m 52 x 26), which

was the first one at Saqqara that Emery excavated (in 1936, see below)

and published (The Tomb of Hemaka, 1938), were impressive and unexpected

at that time for a First Dynasty private burial (only few years later

Emery advanced that S3035 was a royal tomb); despite the contents

of the then already known Covington tomb at Giza (V), those of Tarkhan

1060, 2038, 2050, and Naqada, Egyptologists were nearly unprepared

to the mass of goods which the tomb of Hemaka yielded (now on exibit

in Cairo Museum): vast amounts of pottery (329 with potmarks, op.

cit., 53f., pl. 38-42) and stone vessels (ibid., 55ff., pl. 28-37;

the beautiful but fragmentary schist bowl in form of a feather: ibid.,

pl. 19C), scores of seal impressions of eight different types with

the serekh of Den and the name and titles of Hemaka (ibid., 62-64;

Kaplony, IAF I-III); flint implements (ibid., pl. 11), hard stone

top-game disks (ibid., 28ff., pl. 12-14) one of which with an inlay

hunting scene decoration (JdE 70104); wooden tools, an ebony label

of Djer (ibid., 35ff.), two small ivory labels of Hemaka (ibid.,

39, cat. 412 and 413)

and few more uninscribed wooden labels; an uninscribed roll of papyrus;

a limestone slab with a bull and a monkey painted in black ink (ibid.,

pl. 19D); fragments of wooden boxes (see ibid., pl. 23A for an inlaid

cylindrical one), bags and textiles; ivory fragments of bull leg supports

of a gaming board; some wooden sickles and adzes handles (ibid., 33f.,

pl. 15-16) and nearly 500 arrows of five different types (ibid., 45-48,

pl. 20ff.).

The superstructure of this tomb is divided into 45 magazines; the

substructure consists of a central pit (the burial chamber m 9,5 x

4,9 its floor at more than 9m of depth and at 11,75m from the top

of the mastaba) surrounded by three rooms separately dug in the rock

and accessible through short doorways at the N and S ends of the western

side of the central chamber, the third one at the N end of the eastern

side; at the S of the eastern side there is the lower part of the

stairway: after c. 7m from there it passes in a mudbrick gateway and

13m beyond this one, after three portcullis, the ramp reaches the

ground level, 9m east and off of the tomb niched wall.

S3036 (41x22m) was found by Firth in 1930 (ASAE 31,

1931, 47) and re-excavated by Emery in 1936 (GT I, 1949, 71-81).........

SX (26x12m)

As mentioned above, the reign of Den was the apex of the constructional

'ratio' (in tombs number and in their size); but during the reign

of his successors the tombs, despite of a minor size, did not spare

interesting surprises.

In the reign of Adjib S3338 and especially the cited S 3038

were built; the stepped core of the latter resembled a micro step-pyramid

(cf. above and below).

S3338 (30,5x14m) ..........

S3038

belonged to the official Nebitka (Nebtka). (Emery, ASAE 38,

1938, 455-9; id. GT I, 82-94).

S3038

belonged to the official Nebitka (Nebtka). (Emery, ASAE 38,

1938, 455-9; id. GT I, 82-94).

This tomb was, with S3471 (see above), the most awaited one of Emery's

1949 publication.

It had been cleared in 1936 but the war delayed its publication (GT

I, 1949, containing 8 tombs); Firth had already worked on the superstructure

and burial chamber in 1931 but he didn't arrive to recognize the peculiar

character of this tomb (he died in the same year) which was attributed

to Den's reign by seal impressions of Den and Ankhka.

S3038 was of great importance because it displayed three constructional

phases, in the first two of which the tomb featured a stepped superstructure

which was considered a prototype of the Step Pyramid.

Emery also compared this stepped building with the representation

of Za-Ha-Hor on stone vessels of Adjib's

Heb Sed from Step Pyramid and Abydos X.

The few sealings of Den suggest that it was at the end of his reign

that the construction began, although it must have been concluded

only during the short reign (c. 10 years) of Adjib. Owing to the uniform

size, color and texture of the bricks used all through the three phases,

Emery suggested that the interval between them had to be rather short.

The tomb measured (in Period A) 22,7 x 10,55; N and S of the central

pit, but at an higher level, there were two magazines (on the northern

one there were nine bricked tubular grain bins with a pottery cap

on their top and an outlet at their base; these were blocked by a

stone and covered with Nebitka's mud seal-impressions); from E the

stairway led, after a portcullis, to the burial chamber; another shorter

stairway, just south of the first one, led to a magazine above the

burial chamber; this latter measured 7,8 x4,75 and its floor was 6,10m

from the top of the superstructure.

The eastern façade of the mastaba was vertical, while on the

other three sides there were eight steps looking like a truncated

pyramid: Emery hypothesized (ibid., 84) that perhaps an higher structure

of perishable materials was built on the top of it. The stepped structure

was 2,30m high (preserved up to the top) and faced with fine mud plaster.

An ox, probably sacrificed in this period, was found below the fourth

niche (from N) of the W wall of period C.

In the second phase (Period B) the southern half of the topping terrace

was raised and a wide brick terrace was added around the superstructure,

which thus reached the size of m12,55 x 35 (or more).

In the last phase (Period C) the tomb was provided with the usual

palace façade, and the superstructure partially filled and

subdivided into magazines; in the middle of the N and S façade

a stair gave access to the superstructure.

The two magazines and the burial chamber between them were further

subdivided with mudbrick crossing walls which thus reduced their space.

Finds: the cited seal impressions, 31 stone vessels, flint implements,

some pottery vessels with few pot-marks.

Few meters east of S3038 is S3111 (m29,20 x 12,05) which

Emery found early in 1936 (GT I, 1949, 95-106).

It was dated to Adjib by seal impressions of the official Sabu,

who, alike Nebitka, served under Den and Adjib.

This tomb had no stairway, the superstructure was completely filled

with sand and pottery jars were found in the fill (a custom typical

of Second Dynasty tombs) at the SW corner; north of them Emery found

a nearly 1m high stone platform (m3,60x2,50) of unknown purpose.

An intact subsidiary burial was found in front of the third rampart

(from N) of the western façade of the mastaba.

The substructure pit was 10,45x6m, 2,55m deep below the ground, not

in perfect axis with the external niched wall (few degree W of it);

it was divided in seven compartment, four N and two S of the burial

chamber; this latter was m3,40 (N-S) x 5,40 (W-E).

Although plundered, the burial chamber was found rather in order,

the skeleton of Sabu still in situ (ibid., 98, pl. 40 B,C) within

the remains of a wooden coffin, head to the N (NW) facing W (SW);

some bones had been broken surely by the plunderers in search of jewelry.

There were also stone and pottery vessels (50 pot-mark types), two

boxes for flint knives, arrows, few copper tools, two ox skeletons;

the schist bowl in fragments (Cairo, JdE 71295) is certainly a masterpiece

in the genere (ibid., fig. 58, pl. 40A,B; El-Khouli, Stone Vessels,

1978, n. 5586).

For the subsequent ruler, Semerkhet, no tomb has been excavated

or known at present (but some small one might have existed as Step

Pyramid Complex stone vessels and a potmark

[in: Emery, Hemaka, 54] showing this king's name(s) let us suppose;

nonetheless, given the short reign of Semerkhet, it could be that

no outstanding official died within its course and dignitaries whom

also served Semerkhet, like Henuka,

died and were buried only under Qa'a).

Kaplony (IAF I, 144) cites W.S. Smith's recovery of Firth's excavation

notes containing an hint to a seal impression of Semerkhet (Sesh

Seshat Semerkhet) from FS 3060; Helck (LÄ V, 399)

is probably right in supposing that the tomb and sealing might instead

be of Sekhemkhet's reign (3rd Dynasty).

Emery (GT III, 4) supposed that the lack of tombs dated to Semerkhet

was to be explained in view of the possible unacknowledged position

of this king in the dynastic line: the reuse of stone vessels of Adjib

by Semerkhet and the erasing

of the latter's name by Qa'a was considered a proof of the status

of usurper of Semerkhet (but see instead the series of names Den-Qa'a,

Semerkhet-Qa'a which show no trace of

erasure).

To the end of the Dynasty S 3500 and S 3505 (Emery,

GT III, 1958, 5-36) are dated (reign of Qa'a): S3505

(total size: m65,20 x 40; only the mastaba: m24,15 N-S x 35,10 E-W)

revealed a true proto-funerary temple in the northern side also resembling

the later north-temple of the Step Pyramid complex of Djoser. A stela

found near a niche of the eastern façade revealed the name

and titles of the owner Merka. Other important findings from

this tomb were the bases and feet of two wooden statues found in a

niche of the northern temple; traces of mat-motifs color-paintings

on the palace façade (like those already found in other tombs

as 3506, 2405); the presence of a very simple

pattern of niches on the western wall of the tomb, whereas the other

three sides were built with the usual complex design; some clay bull's

heads with real horns laying on the base of the bench surrounding

the niched walls (like those found in Sekhemka S3504); finally, among

the stone vessels fragments and the jar mud seal impression, an incised

vessel with the name of the mysterious king Seneferka and a

sealing which could not be attributed to anyone of the rulers known

from that period (Cf. here for both these

obscure sovereigns).

S3500

(37,10x23,35m) This late 1st Dynasty (reign of Qa'a) was found by

Emery in May 1946 between S2185 and the escarpment edge; it already

shows further signs of the transition towards the 2nd Dynasty architectural

forms; the most evident one is the presence of only one niche on the

façade, at the south end of the eastern side; the rest of the

superstructure is plain like the enclosure wall around it; this latter

is open on the SW corner. The plan/section

of the tomb can give a good idea of its general layout, but some characteristics

must be here evidenced, namely the presence of only four subsidiary

tombs on the southern side of the superstructure (partly underneath

the S enclosure wall): their aspect differs from that of the early

and mid 1st Dynasty retainers' burials, because they have a "leaning

barrel vault", which is the earliest evidence presently known

in Egypt of brick vault roof (cf. figure; other later examples are

the archway passages of 3rd dyn. mastaba K2 at

Bet Khallaf).

S3500

(37,10x23,35m) This late 1st Dynasty (reign of Qa'a) was found by

Emery in May 1946 between S2185 and the escarpment edge; it already

shows further signs of the transition towards the 2nd Dynasty architectural

forms; the most evident one is the presence of only one niche on the

façade, at the south end of the eastern side; the rest of the

superstructure is plain like the enclosure wall around it; this latter

is open on the SW corner. The plan/section

of the tomb can give a good idea of its general layout, but some characteristics

must be here evidenced, namely the presence of only four subsidiary

tombs on the southern side of the superstructure (partly underneath

the S enclosure wall): their aspect differs from that of the early

and mid 1st Dynasty retainers' burials, because they have a "leaning

barrel vault", which is the earliest evidence presently known

in Egypt of brick vault roof (cf. figure; other later examples are

the archway passages of 3rd dyn. mastaba K2 at

Bet Khallaf).

These are the latest remains of the "barbaric custom"

of servants sacrifice at Saqqara; the later tombs didn't show similar

subsidiary burials, whereas it seems that few retainers were still

slain at Abydos in the late Second Dynasty royal tombs. Three of the

four subsidiary tombs were found intact and the westernmost ones (n.

1 and 2) still had the dead bodies (a middleaged man and an old woman;

head to the S facing W) wrapped in linen within the coffin; each one

had a foreign flask and a wood cylinder seal (one uninscribed and

another one with faint painted inscr.).

Another interesting feature is the magazine in the northern part of

the superstructure: it was divided in two parts, the W one filled

with wine jars and the E one containing model clay granaries/bins

and jars (see fig., upper-center).

More jars were found in the filling or on the floor of the burial

chamber along with stone vessels.

The burial chamber is accessed by a stepped passage from east (provided

by two small side-magazines and two portcullis) and it consists of

a E-W rectangular (8,10x5,40m) pit without any internal subdivisions.

Few objects were found apart from vessels: some flint blades and seal

impressions; these latter bore the serekhs of Horus Qa'a and the titles

of a xrp Xrj-ib and nbj; one had a possible personal name Sn-Neith

(GT III, pl. 124, 3).

SX (see above)

S2120

S2121

In 1995 M. Youssef Inspector of Antiquities at Saqqara made

some sondages on a late(?) First Dynasty mastaba only 50m NW of the

Inspectorate office (Youssef, GM 152, 1996, 105-111).

This large tomb (unnumbered) SCA 1995 (c. 51x27,5m)

was found c. 40m W of S3507 which was considered to be the southernmost

of the North Saqqara necropolis; SCA 1995 is thus not on the edge

of the escarpment but it occupies the second row of tombs (directly

at few more than 100m S of S3505) and actually it is it the southern-most

archaic tomb known at N Saqqara (its southern wall c. 20m south of

that of 3507; cf. ibid., fig. 1).

The niched wall is 4,79m thick (c. 1m deep niches) and it was surrounded

by one (?) plain enclosure wall; on the north side it seems to exist

a possible parallel with the S3505 funerary temple (ibid., 106f.)

and also the sheer size of the tomb and that of its bricks (0,23 x

0,11 x 0,07m) point to a date to the reign of Qa'a.

Contrarily to most of the North Saqqara tombs (and certainly to all

those in the 1st Dynasty easternmost rows) this tomb showed signs

of having been built over by Graeco-Roman period burials of children

in small wooden coffins and some dogs in baskets. Pottery of late

period was also found along with older stone vessels and other objects.

In 2003 a more thorough excavation was carried out, revealing interesting stone vessels fragments with the incised serekh of Sneferka/Neferkaes, which haven't been published yet.

I am inclined at least to suspect that the southernmost limit of the

archaic necropolis might also have not been that of tombs SX, S3507

and SCA 1995, and that, perhaps, the cemetery continued up to N of

the wadi c. 200m SE of Teti's pyramid (on the latitude of the pyramid

of Userkaf) where the ground looks still good for building: there

are Late period brick walls, the destroyed pyramid Lepsius XXX and

a Stone Mastaba; but indeed the same presence of these structures

could also be a sign that the Archaic cemetery didn't prosecute beyond

the Inspectorate offices: as we have seen, with very few exceptions

(i.e. SCA 1995), the First Dynasty tombs were not overbuilt in later

periods; furthermore, at the time of the construction of the Inspectorate

Office and magazines any older structure encountered would have been

signalled, as it happened in 1937-8 with tomb SX (see above).

Auguste Mariette (1821-1881) was the first one

to carry out 'scientific' excavations at North Saqqara after the explorations

of the period of Vyse and Perring and the more recent Prussian expedition

of Lepsius (1845).

In 1950 Mariette discovered the Serapeum where the Apis bulls were

buried and ten years later he made further astonishing discoveries

as the Old Kingdom mastabas of Ka-Aper (with the wooden statue of

the "Sheikh el-Balad"), Ranofer, Hesira (see below) and

Ti (among the most beautiful ones as far as decorations); Mariette

also carried out excavations to the north of the Djoser complex (where

Sheri's mastaba B3 must be located) and even

in the North Saqqara plateau; most of his posthmous 1889 publication

was devoted to Old Kingdom tombs (espec. Dyn. IV-V), but some earlier

tombs were also included like the mentioned tomb of Hesi (MM A3) and

MM A2 (= S3073, twin mastaba of Khabawsokar and Hathorneferhotep,

cf. id., Les Mastabas, 1889, 71-79; N. Cherpion, Or. Lov. Period.

11, 1980, 79-90; M. Murray, Saqqara Mastabas 1905; panels Cairo Museum,

CG 1385-87).

Almost certainly Mariette worked in the North Saqqara eastern slope

as well; Emery noticed that traces of modern excavations, possibly

accomplished by Mariette or on his behalf, were found during the clearing

of S3505 early in 1954 (Emery, GT III, 11); this was the only N. Saqqara

tomb of the 15 extensively published by Emery to produce any remains

from previous archaeological activities.

In this period the interest was equally devoted onto the Step Pyramid

which had been re-explored by Lepsius and which surrounding complex

was still unknown; Mariette made an interesting discovery in one of

the galleries beneath what was later known to be Djoser's complex

North Court (western part): in the tomb MMA4 (= n. 86) (Les

Mastabas, 83-86; PM III², 415) he found two alabaster tables

with lions heads, probably used to embalm single organs as viscera

(Cairo Mus. CG 1321; for the galleries see also Firth, ASAE 28, 1928,

82-83, pl. 3; Lauer, PD I, 1926, 185-186; id. PD III, 1939, pl.

22, shaft c). A4 dates to the latter part of the Second Dynasty.

A similar gallery, but with E-W orientation, was found in the same

court some meters north of A4 entrance (Firth, ASAE 27, 1927, 107f.;

Lauer, PD I, 183ff., fig. 208; Lauer, PD III, pl.

22, shafts P8-P9; PM III², 415): seal impressions of Khasekhemwy

and Netjerykhet and large amounts of bread and fruits were found in

it.

Almost fifty years after the work by Mariette, James Edward Quibell

[photo](1867-1935), who had made

experience working in 1895-1900 at Naqada and Ballas and at Hierakonpolis

and El Kab, became the Chief Inspector of Saqqara (1911).

In the first part of the Second Dynasty we find some of the largest

tombs of the Northern necropolis (reign of Njnetjer) as S 2302 and

S 2407: many of these mastabas were excavated by Quibell in 1911-1914

but published (all except Hesyra's 2405, see below) only ten years

later, after the war (Excavations at Saqqara 1912-14. Archaic Mastabas,

1923; Quibell cleared the tombs in sectors D1 to F2 and G2-G3 of this

general plan).

The archaeological standards (both in excavation as in publication)

were indeed somewhat far from those of the next generation of Egyptologists

like Lauer and Emery (and also from those of his old master Petrie

and from those of F.W. Green); furthermore, despite the notes Quibell

took at the time of the works, the long forced delay in the publication

certainly didn't play in favour of his memory.

The 1st World War stopped the excavation at Saqqara for 15 years,

until Cecil Mallaby Firth [photo]

(1878-1931) was entrusted to reopen them; in 1927 he was appointed

Chief Inspector of Saqqara. Firth had already acquired many years

of experience during the First Archaeological Survey in Nubia 1907-1911

(he published with G. Reisner several very important A-group cemeteries)

and he later began the clearing and exploration of the Step Pyramid

complex (published with Quibell after his death: Step Pyramid, 1935;

also cf. his reports in ASAE 1926-1927 in bibl. below); early in 1930

Firth had begun to clear some Archaic tombs of the North Saqqara plateau

(ASAE 31), in view of the masterpiece on the OK tombs development

which G. A. Reisner was preparing (Reisner, Tomb Development, 1936);

but Firth died in 1931 and only a small part of his notes were recovered

by Reisner, W.S. Smith (who planned for Reisner in 1933 the most imposing

tombs known) and W.B. Emery (FS 3035, FS3036, FS 3038, FS3041 had

been discovered by Firth); but most of Firth's work results unfortunately

remained unpublished.

The same fate attended Quibell who had moved to the Step Pyramid Complex

after the war: he died in 1935.

In 1935 Lacau's, Firth's and Quibell's inheritance of the excavation

of the Step Pyramid Complex was definitively handed down to J.P. Lauer

(whom had started working there, still a young boy, since the 2nd

excavation campaign in 1926; see below), while Quibell's and Firth's

task at North Saqqara passed into the hands of Walter B. Emery.

WALTER BRYAN EMERY (1903-1971)

[ Click here for the page

of W.B. Emery]

Egyptologist Walter Bryan Emery was born in Liverpool

on July 2, 1903. Before his career in Egyptology started he had

been addressed by his parents to the Marine Engineering, where

he learnt the principles of draughtsmanship which will be brilliantly

exploited into the line drawings illustrations of his books plates.

In 1923 he participated to the EES excavation campaign at Amarna

as student assistant thanks to a recommendation by T.E. Peet.

In 1924 he was already Field Director of sir Robert Mond's Excavations

at Thebes for the Liverpool University.

He made several clearings, restorations and protective operations

into a score of tombs at Sheikh Abd el-Gurnah and in the following

years, a 22 years old boy, he was directing four hundred men for

the clearance and restoration of the wonderful tomb of the Town

Governor and Visir Ramose (TT 55); few years later he also drew

the fac-simile of Ramose's tomb reliefs which easied the task

for Davies' publication.

In 1927-28 he worked, still for R. Mond, at Armant where he discovered

the Buchis bulls catacombs: it was Emery's first animal necropolis

before the long series he'll excavate at Saqqara in the last ten

years of his life.

The following season he joined H. Frankfort in the excavations

at Armant where Emery was accompained by his wife Molly, married

in 1928. In the six following years they were together in Nubia

for five campaigns of rescue of sites and monuments after the

construction of the new Aswan dam. The most amazing and difficult

task proved to be the research (1931) on the Tumuli of Ballana

and Qustul, which it was still doubt whether they were natural

formations or artificial mounds. The IV-VIth century A.D. X-Group

kings who ruled Lower Nubia after the fall of Meroe had been buried

beneath those mounds with their wooden chests, weapons, glass

vessels, furniture, silver harnessed horses and camels, sacrificed

servants and wives (The Royal Tombs of Ballana and Qustul, 1938).

The Nubian survey ended up in 1934 and in the following year his

presence was requested at Saqqara where he was asked to continue

the excavation of the archaic cemetery interrupted four years

before on C.M. Firth's demise.

At Saqqara Emery started in 1935 from tomb FS 3035, which Firth

had only partially cleared (cf. the plan in Reisner, Tomb Development);

for the first time it was shown that, unlike most of the 2nd and

3rd Dynasty mastabas dug by J. E. Quibell before the war, the

First Dynasty tombs contained magazines even in their superstructure:

FS3035 had 45, and many still contained part of their original

provisions (cf. above).

Emery estabilished with P. Lacau that, after the recording of

the loose tombs which Firth had commenced to dig, "only the

systematic clearance of the whole site square by square"

could do justice to such an important cemetery.

More tombs excavated or re-excavated in 1937-39 were published

by Emery only after the Second World war (GT I, 1949): S3036,

3111, 3038, 3120, 3121, 3338, X (also cf. GT III, 1958, 1-2).

In 1938 he had also discovered S3357, the oldest tomb known at

Saqqara, which was soon published in the next year (Hor Aha, 1939);

this publication opened the famous dispute between those who thought

that the Early Dynastic kings were buried just in those tombs

at Saqqara (the Abydos tombs being regarded as mere cenotaphs)

and those who instead still shared Petrie's view maintaining that

Abydos was the royal cemetery (see above).

The last find/excavation before the war was S3471, which contained

an incredible quantity of copper (cf. above).

After the war, Emery found (in 1946) the mastabas S3500 and 3503;

in the following 7 years the works were stopped.

For a short period Emery dedicated to the diplomatic career; then

he obtained the Chair of Egyptology at University College, London

in 1951 and he was appointed Field Director of the EES in 1952;

in 1953 the fieldwork at Saqqara were started once again.

In this period he excavated S3503 (discovered in 1946), and found

four new tombs: S3504, S3505, S3506 and S3507 (published in GT

II/III, 1954, 1958). S3507 was the last mastaba of the 1st Dynasty

excavated on the eastern ridge of the North Saqqara plateau; in

the last 7 years of his life Emery worked on the other side of

the plateau (see below).

Unfortunately the whole complex of 'minor' tombs, e.g. the smaller

ones of First Dynasty date and those of the Second and Third Dynasty,

which Emery had worked at during the 1933-1939 / 1945-1947 seasons,

have never been published at all (see Archaic Egypt, 158-164,

figs. 94-97).

From 1956 to 1964 he was in Nubia for the salvage campaigns (7

seasons) of the sites and monuments threatened by the High Dam

of Aswan. It was in these years that he published two divulgative

and interpretative books: Archaic Egypt (1961) and Egypt in Nubia

(1965); in 1962 he published a small report on the Second Dynasty

tomb 3477 in which an intact funerary repast had been found (A

Funerary repast, 1962).

He was finally back to North Saqqara in October 1964; he found

some Third Dynasty mastabas on the western part of the Northern

plateau, where he discovered the tomb of Hetepka (published by

Martin in 1979) and the Ibis galleries; in these years he began

to think that there could have been a relation between these animals

necropoleis and the Third Dynasty mastabas, perhaps a possible

indication that the seat of the tomb of Imhotep should

have been very near; in 1967 Emery was operated but forty days

later he was already beginning a new work season; in 1968/9 he

cleared and planned a large (m 52x19) 3rd Dynasty twin Mastaba

(S3518, Djoser's reign) and the Baboons necropolis; next year

the catacombs of the falcons and those of the cows, the Mothers

of Apis bulls, together with large amounts of late period objects

were brought to light; in 1970-71 it was the turn of a new Ibis

catacomb and more nearby tombs of the Third Dynasty: S3050, S3519

(cf. Emery's reports in JEA 51-57; Martin, Smith, Jeffreys in

JEA 60, 63); but in the last five years his health conditions

had often been difficult and only his character strength allowed

him to pursue day by day in the work which he had loved for all

his life. Few days before the end of the 1970-71 season he lost

consciousness after the morning work and died four days later

in the night of March 11, 1971 (H.S. Smith, in: JEA 57, 1971,

190-201); Emery was the most important figure working and

walking through the North Saqqara plateau in the middle of the

last century, his contribute to the knowledge of the Early Dynastic

period was perhaps second only to J.P. Lauer's, whose name was

still more indissolubly tied to the necropolis of Saqqara; both

these men shared a profound affective attachment to this site,

an indefatigable will to tear the past out of the its sands and

an undoubt professionality in undertaking their work and documenting

it with very high standards of publication.

The EES works at North Saqqara were prosecuted for some years

by G.T. Martin and H.S. Smith; in 1976, when the excavations were

definitively closed, the EES declared that (apud J. D. Ray, WA

10:2, 1978, 151) the "mummified zoo" which Emery and

co. had discovered amounted to 4 million mummified ibises, 500.000

hawks, 500 baboons, 20 cows, 4000 dedicatory statues, about 1000

documents in demotic and other texts in Greek, Aramaic, Coptic,

Carian, Arabic and an unknown language using the Greek alphabet;

not to count the terraced temples and the tombs.

But for us the most precious inheritance he's left is certainly

the series of sixteen First Dynasty tombs wonderfully published

in five books, twenty years of professional excavations at North

Saqqara East (1936-1956), a number of articles and reports (esp.

in JEA, ASAE and The Illustrated London News), the first synthesis

of the Archaic Egypt culture and a clear example of full dedition

to the passion of a life by one of the greatest names of Egyptology

ever. |

PART III: SECOND DYNASTY MONUMENTS

The Second Dynasty private tombs development initiated with

the end of the previous Dynasty; under Qa'a the pattern of niches

gradually simplified and the superstructure began to lack magazines

(cf. S3024, in GT I).

The main characteristic of the tombs of this period were thus the

plain façade with only two niches on the east (the southern

one being the larger which will increase in size and complexity),

the lack of enclosure wall, lack of rooms in the superstructure (although

some tombs had small rectangular tank-like compartments of mudbrick

or large quantities of pottery loosely deposited in the gravel and

rubble filling of the mastaba, cf. Archaic Egypt, pl. 12-13; Quibell,

Archaic Mastabas: pl. 15, S2171; pl. 16, S2105; pl. 20, S2322); the

ramp's side-storerooms were moved down becoming true rooms and the

whole substructure was now carved in the rock. It generally had a

stairway to the east (starting from within the floor of the filled

mastaba) which after some meters curved of 90° southwards; heavy

limestone portcullis lowered from above blocked the main corridor

which branched off with storerooms; at the southern end of the gallery

there was the latrine and lavatory on the left (the relationship between

tombs and houses is still more stressed) while the burial chamber

was generally on the western part of the main axis extremity.

In this period the wooden coffins (Archaic Egypt, pl. 24-25) still

retain the niched aspect and the earliest traces of mummification

practices appear: the bodies are not only wrapped in lined bandages

(as the forearm with bracelets found by Petrie in Umm el-Qaab O) but

the characteristical parts of the body are modelled over and beneath

the wrappings by soaked substances (ibid., 162f.).

Most of the dated tombs of this period were built during the long

reign of Ninetjer as the large S2302 (Nirwab),

2307, 2337 and several smaller mastabas like S2171,

2498, 3009, 2429 (Khnwmenii) (cf. plans

and discussion of these tombs in the page of Ninetjer);

these tombs were cleared in 1912-1914 by Quibell and published in

form of a summary report ten years later (Quibell, Archaic Mastabas,

1923).

S3014 was dated to Wneg by three

stone vessels found in it by Firth (PD IV.2, 53, fig. 5).

S3477 of a (late?) Second Dynasty princess Shepsesipet

(CdE 27, 1939, 263-265; Emery, A Funerary Repast, 1962; id., Archaic

Egypt, 1961, 243-246, pl. 28-29; Helck, LA V, 391, 399; PM III²,

444) contained a complete funerary repast and a stela (Emery, op.

cit., 1961, pl. 32a; Kaplony, KBIAF, 1966, 104, Stela 35).

The same characters of the largest tombs of this period

(Ninetjer's reign) were noticed, but at a higher size and degree of

complexity, in the explorations of the early Second Dynasty Royal

tombs of Hotepsekhemwy and Ninetjer, located in the first part

of the XXth century; tomb

A was first discovered by A. Barsanti in 1900,

while S. Hassan (1938) was the first to enter Ninetjer's tomb

B; they are located south of the Step Pyramid complex

southern wall; recently one more (tomb

C) has been discovered further south near Horemheb's one,

probably to be dated into the middle of the Dynasty; it was reused

for Meryneith burial in the NK (excavations in 2001-2002 by R.

van Walsem and M. Raven; see the link below); the possibility

of the presence of more royal tombs of the Second Dynasty in this

area had already been suspected; in recent years the area between

tombs B and C has been the site of interesting finds, like the brick

inscribed with Nefer-Senedj-Ra cartouche name

and an alabaster vessel with Hwt-Ka Hrw Za (alike other found in the

Step Pyramid; see Wneg).

J.P. Lauer published a plan of tomb A in 1936 (PD I, fig. 2),

while only the 1990s explorations by P. Munro have produced

the first (partial) plan of tomb B (Kaiser, in FS Brunner-Traut, 1992,

167-190, fig. 4d).

Seal impressions of Nebra were found

by Barsanti in tomb A (Maspero, ASAE 3, 1902); the famous stela now

in Metropolitan Museum was discovered in Mit Rahina where it was used

as threshold of a house and published by H. G. Fischer (Artibus Asiae

24, 1961; cf. Lauer, Orientalia 35, 1966).

For details and figures of tomb A: Hotepsekhemwy;

for tomb B: Ninetjer; for tomb C: New

Royal Tomb; cf. the discussion in the Second

Dynasty introduction. (See also bibl. W. Kaiser, 1994).

The remaining part of the Second Dynasty has left but

few traces at Saqqara; this obviously reflected the difficult period

the state was undergoing; there seems to have been an important reprise

of building activity in the reign of Khasekhemwy,

although only few minor private (unpublished) tombs can be dated to

his reign (S3034, S3043).

I have already hinted above to the two main galleries found within

the NW part of Djoser's complex; the

material from these underground structures, both that found by Mariette

in MM A4 as well as the seal impressions from the northern one, dated

to the reigns of Khasekhemwy and Netjerykhet.

The vast NS tunnels and side chambers beneath the Step Pyramid Complex

Western Massif were explored by Firth and (perhaps too) accurately

planned by Lauer (PD I, fig. 206; PD III, pl. 22); R. Stadelmann (1985)

voiced the possibility of these being the underground parts of previous

rulers' tombs, noting the similarities with Hotepsekhemwy's tomb.

These dug out substructures were related by Stadelman (ibid.) to the

fainted stone constructions in West Saqqara, the best known of which

is the Gisr el Mudir (see pictures on

top of this page).

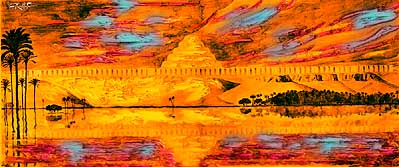

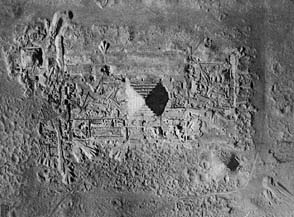

THE ROYAL ENCLOSURES IN WEST SAQQARA

Gisr el Mudir (Enclosure of

the Boss), (650x400m) is the oldest construction presently known

to have been built with such a massive use of stone masonry (Maragioglio-Rinaldi,

APM II, 53; Spencer, Orientalia 43, 1974, 3; Swelim, Some Problems,

1983, 33ff.; JEA 79, 1993 cit. below; Mathieson et. al., JEA 83, 1997,

17-53; JEA 85, 1999, 36-43).

The walls size is enormous for extension and thickness (more than

15-17m thick, covered by two parallel stone masonry embankments filled

with rubble and sand; such a wall, now preserved up to the 15th course

of stone in the NW corner 4,5/ 5 m high, had to be originally -or

in the builders' aim- at least 10m high); the enclosure total size

is about 650 x 400m (cf. Djoser's Step Pyramid Complex which measures

"only" 544,9 x 277,6m , thus being few more than half the

area of Gisr; this latter is also 4 times the area of Sekhemkhet's

complex).

The perimetral course of the Gisr el Mudir was first noticed by Perring

and later recorded by Lepsius. It was then also marked on De Morgan's

Carte de la Necropolis Memphite (1897) but for many years it

remained a riddle;

it was thought to be a further unfinished 3rd dynasty Step Pyramid

complex, a funerary enclosure like those at HK and Abydos, a cattle

precinct, or a military fort (barracks) for the guarding and patrolling

of the necropolis.

The first excavation was carried out by A. Salam Hussein (the Boss,

because then Director of the E.A. Service) in 1947-48; these remained

unpublished (but cf. Swelim, loc. cit.). W. Kaiser pointed the attention

onto the Abydos Talbezirke which became object of further researches

(Kemp, JEA 52, 1966; Kaiser, MDAIK 25, 1969; Kaiser-Dreyer, MDAIK

38, 1982; Stadelmann, op. cit., 1985; O' Connor, JARCE 26, 1989) while